Why America is Hooked on Drugs

As any medical advertising writer knows, you don’t need much to turn a sow’s ear into a silk purse. For example, I once had a writing assignment for an extended-release oxymorphone. The client told me to say their drug had a low likelihood of being abused. There was no clinical evidence to back up the claim. Instead, we implied less abuse potential by providing doctors with pharmacodynamic data showing that the new formulation was absorbed into the blood stream more slowly.

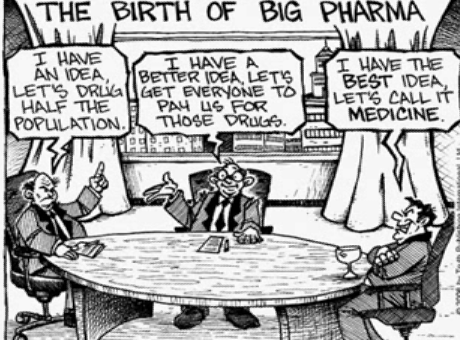

While print and digital advertising contributes to overtreatment, more insidious is the way marketers exploit scientific publishing, guidelines and industry-sponsored CME (continuing medical education). This is accomplished through the use of key opinion leaders, also known as thought leaders.

The opioid epidemic is a classic illustration of how this occurs in American healthcare. A look back at Purdue Frederick’s marketing strategy continues to be a template for building markets for drugs for cancer, diabetes, and rheumatology.

Building a blockbuster brand

The FDA approved short-acting oxycodone in 1950. For 40 years, prescribing of short-acting oxycodone was limited to pain management specialists and oncologists. This changed in the early 1990s as drug companies prepared to launch long-acting opioid medications. To create demand for their new products, companies set out to persuade physicians that long-acting opioids were safe for all kinds of pain.

Purdue Pharma* had particularly ambitious sales goals for the long-acting opioid, Oxycontin. Purdue’s key strategies: 1) promote Oxycontin to primary care physicians, expand use to conditions like low back pain, osteoarthritis, dental pain and migraine; 2) provide evidence that long-acting oxycodone had less abuse potential than its short-acting counterpart; and 3) overcome public health concerns about addiction. Sales of long-acting Oxycontin quickly exploded: from $45 million in 1996 to almost $1.5 billion in 2002.

How did this explosive growth occur?

- Purdue’s ‘Partners Against Pain’ website stated that long-acting opioids were safer for chronic pain than non-steroidal anti-inflammatories, muscle relaxants or tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs).

- Sales reps told physicians that there was “less than one percent” risk of addiction with Oxycontin, while handing out 34,000 Oxycontin patient coupons to encourage prescribing.

- Purdue distributed 10,000 reprints of an article falsely stating that Oxycontin rarely caused withdrawal symptoms, even when abruptly discontinued.

Leveraging physician influencers

Purdue’s use of KOLs was more instrumental than advertising to Oxycontin’s phenomenal growth. KOLs are academic physicians hired by drug marketers to educate their physician peers about the company’s products. These thought leaders represent the company’s point of view at medical conferences, at dinner programs, on guideline committees and before government and accreditation organizations. While some KOLs compromise themselves for status and money, many are pawns in a game they do not fully understand. Manufacturers of opioids like oxycodone and fentanyl paid KOLs more than $29 million in speaking fees and honoraria in the two-year period (2013 – 2015).

The FDA approved oxycontin in 1996. Within the year, Purdue started funneling millions of dollars to two pain organizations, the American Academy of Pain Management (AAPM) and the American Pain Society (APS), both headed by Russell Portenoy, M.D, a pain management specialist at Beth Israel Medical Center. His two pain management groups aggressively advocated for removal of restrictions on opioid prescribing. As early as 1997, AAPM and APS dismissed concerns expressed by those who feared lenient prescribing of opioids would lead to a public health crisis of addiction. The AAPM and the APS also crafted national pain management guidelines recommending opioid use for chronic non-cancer pain. Both pain organizations lobbied state medical boards and the Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations (JCAHO) to implement these new pain management standards. What was the evidence supporting the low abuse potential claims? An article, “Chronic use of opioid analgesics in non-malignant pain: report of 38 cases”, published by Russell Portenoy and Kathleen Foley of Cornell University Medical College. The paper became the bedrock of evidence supporting use of chronic opioid therapy for non-cancer pain.

Criticism of low abuse potential

Pushback against the low abuse liability claims sprang up soon after the launch, however had little impact on practice . In 2009, the APS and the AAPM – responding to criticism about their links to opioid manufacturers – updated their recommendations. Their new guidelines however rehashed the original ones and stated, “the likelihood that treatment of pain using an opioid drug which is prescribed by a doctor will lead to addiction is extremely low.” As late as 2010, almost 90% of APS funding came from opioid manufacturers.

Shifting sales overseas

As media scrutiny intensified, Dr. Portenoy disassociated himself from Purdue. In reaction, Purdue created its own pain advocacy groups in 2011 – RxSafetyMatters and RxPatrol – to work with police, legislators and healthcare professionals to prevent abuse and diversion. However, as concerns about opioid abuse continued to grow in the United States, Purdue shifted their focus overseas. Today, Purdue sells oxycodone in 51 countries through MundiPharma. Former U.S. Food and Drug Administration commissioner David A. Kessler has accused Purdue of following Big Tobacco’s playbook. “As the United States takes steps to limit sales here, the company goes abroad.”

The opioid epidemic is just one example of how drug marketing contributes to overtreatment. How can society protect itself from these types of public health crises? Under the current system, I doubt it can. Until medical professionals and consumers better understand how commercial forces shape the practice of medical care, history is doomed to repeat itself.

*Formerly Purdue Frederick.

5 Comments

Excellent research & article. My concern is that it is too long and not directed more specifically towards patients(patient handout), or to medical students & doctors. A patient handout could circulated thru medical journals—if they are not afraid of losing ad $. JAMA has a page dedicated to patient Ed I used to cut out for my office. Might be worthily to look into an online pop-up version sponsors might support— like AAFP, etc. keep on keeping on. This a tough nut to crack!

Thanks for this very informative article about how the opioid epidemic was created. Addiction to Oxycontin probably contributed to the untimely death of one of my best friends. The drug rapidly became less effective at reducing his pain. He was prescribed the maximum dose at the minimum interval until he died in his 50s.

Great article! Now that the opioid crisis has become a very public topic of discussion (finally), it could be a great starting point from which to educate people about big pharma abuse in general. Maybe now more people will listen. Keep writing, Lydia!

The two big changes in healthcare was 1) making it legal to profit from it and 2) making it legal to advertise direct to the patient. In fact… I should really say “consumer” here, because that is exactly how Pharma looks at a patient… just another consumer to exploit. Thank you for sharing this piece and helping uncover the atrocities of what happens when capitalism is left unchecked in healthcare (which should never be a “free market” environment in my opinion)!!!!

Interesting. In the long run, the opioid epidemic is yet another symptom of a larger problem in medicine–the influence of money on clinical decision making and prescribing habits.

Topics

Share